- A Majerteen Darod Somali man (Cushitic).

- An Afar woman (Cushitic).

- A Benadiri Somali man (Azanian Cushitic origin).

- A Saho woman (Cushitic).

- Rashaida Arab children (Semitic).

- An Oromo woman (Cushitic).

Posted in Home

11 Saturday Mar 2023

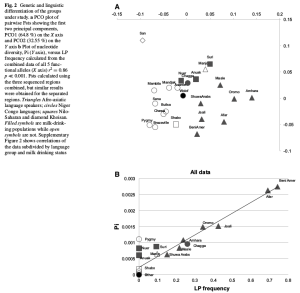

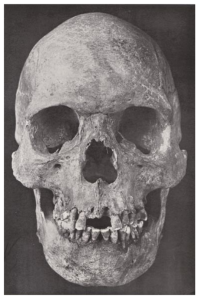

The ancestral origin of the Afro-Asiatic-speaking groups inhabiting the Horn of Africa has long been a subject of debate among scholars. In the 2000s, with the advent of genomics, a number of scientists proposed that these communities were formed through contact between ancient West Eurasian and Sub-Saharan African individuals. They principally based this on admixture analyses, which compared the genomes of persons from various reference populations with those of Afro-Asiatic speakers from the Horn region. The earliest of these genomic studies typically used modern Europeans and modern West Africans as their proxy groups. However, as more global populations were analysed, it became clear to researchers that virtually every living individual is mixed to some degree, thereby making contemporary groups inadequate reference populations for genomic analysis. This realization prompted scientists to increasingly turn to ancient specimens, which they assumed — usually correctly — would be less admixed than modern individuals and therefore more reliable proxies.

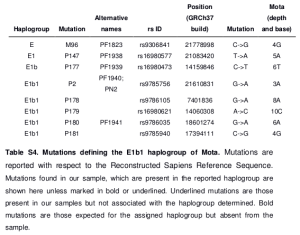

Llorente et al. published one such paleogenetics study in 2015, analysing for the first time an indigenous hunter-gatherer from the Horn (see Ancient DNA from Ethiopia). At the time of publication, this forager individual, called Mota, was believed to be “purely” African and thus free of non-African admixture. Subsequent examination found that there, in fact, had been a software-related error; the specimen apparently did harbor some Eurasian ancestry, albeit a trivial amount (cf. Erratum). Consequently, researchers on the genetic affinities of the Horn’s Afro-Asiatic speakers continued to utilize Mota as their favored ancient Sub-Saharan African proxy, with newly-analysed early Levantine populations (viz. Mesolithic Natufians, Pre-Pottery Neolithic makers) serving as their preferred stand-ins for West Eurasian ancestry.

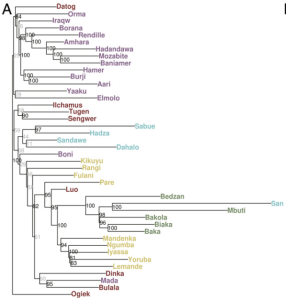

In 2020, Wang et al. released an archaeogentics paper that included a number of never before analysed ancient specimens from eastern Africa. These newly-published samples helped unveil several layers of ancestry in the Mota forager, which had previously been hidden. Mota’s ancestral makeup was revealed to actually consist of various hunter-gatherer elements (Hadza, Mbuti and Khoisan-related components), as well as minor Niger-Congo/Nilo-Saharan-related admixture and considerably higher Eurasian admixture than previously had been realized (~25%). Additionally, genome analysis found that the earliest Afro-Asiatic-speakers yet to be analysed in eastern Africa (i.e. the Cushitic settlers of the Pastoral Neolithic) carried a predominant West Eurasian ancestry related to ancient North African/Levantine groups, with ancillary Sub-Saharan African admixture. The analysis also showed that a 300 BP individual from the Kakapel site in Kenya bore the most such Sub-Saharan African ancestry, thus supplanting Mota as an ideal proxy (cf. Supplementary Material).

Thanks to these new samples, we can now estimate with much greater accuracy than ever before the actual ancestral composition of the Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations from the Horn of Africa.

Admixture Analysis

To assist us in this endeavor, we will make use of the Vahaduo Admixture JS program, which interprets data from the official Global25 datasheets. Global25, or G25, is a powerful genetic system originally developed by the Eurogenes project. Based on Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCA) coordinate data, it allows users to compare the genome of any modern or ancient individual against that of well over 6000 ancient samples culled from around the world, as well as several thousand modern samples.

According to Genoplot:

Global 25 (G25) ancestry modeling is currently the most effective way to perform free-form discovery of ancestry. The set of coordinates used by Global 25 are a product of Eurogenes. They were created as a means to facilitate ancestral admixture modeling[…]

This type of ancestry modeling allows for very precise and granular determination of ancestry. Unlike admixture calculators which come locked-in to pre-defined ancestral components, G25 modeling allows for selection of any number of potential ancestral sources.

Furthermore, through its Single function, Vahaduo has the capacity to cross-analyse thousands of genomes in a matter of minutes. This gives it a distinct advantage over other genetic modeling programs, which typically can only process a handful of genomes at a time. As Bulbul and Kidd (2021) note, the accuracy of an autosomal SNP analysis is dependent upon which reference populations have been selected and the sample size of each of those reference populations. If a key reference population has been omitted from study or if a selected reference sample is too small in terms of the number of individuals in contains, the results produced will be incorrect and unrepresentative. It is therefore imperative for accurate ancestry estimation to have as large as possible a global coverage of reference populations:

One can only estimate an individual’s ancestry among the existing reference populations. Initially, a panel of SNPs is good only for the set of populations used to select the SNPs. As more populations are tested, the SNP panel may have broader applicability. Basically, the inference of ancestry can only be as good as the global coverage of the reference populations and the reference populations need to provide reasonable estimates of the allele frequencies of all the SNPs in the specific panel of SNPs.

Hence, Global25 ancestry modeling is the best tool for our genome inquiry.

Step 1: Identify the “purest” Sub-Saharan African reference population available

As a first step in our genetic investigation, we will try and determine which ancient Sub-Saharan African population the contemporary Nilotic peoples share the most affinity with. We are specifically interested in such individuals because genome analysis by Prendergast et al. (2018) and Wang et al. (2020) shows that the Cushites of the Pastoral Neolithic absorbed an African population carrying ancestry similar to that borne by modern Nilotes.

We begin by running a Vahaduo Admixture JS Distance analysis on the ancient African samples listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet. In order to not invalidate our findings, these Source populations must exclude any ancient specimens possessing substantial Eurasian ancestry (viz. the Pastoral Neolithic, Kulubnarti, Pastoral Iron Age, Kenya Iron Age, ancient Egyptian, ancient Moroccan, Guanche and Zanzibar Euro specimens). For our Target populations, we will employ all of the modern Nilote samples listed on the Global25_PCA_modern datasheet. The resulting Vahaduo Distance analysis, shown here, indicates that every single Nilotic sample (except for one heavily mixed Datog individual) shares greatest genetic affinity with the Kakapel 900BP cohort from Kenya.

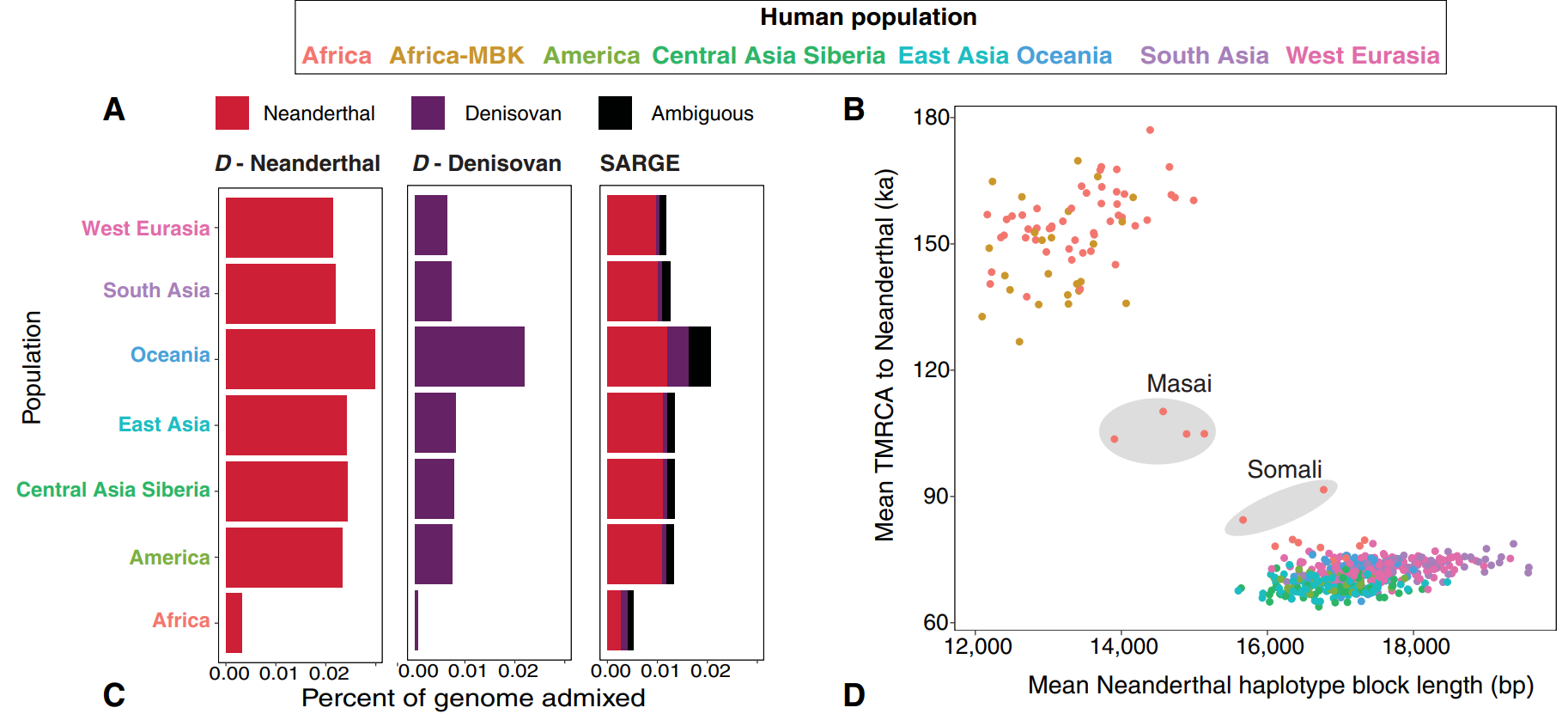

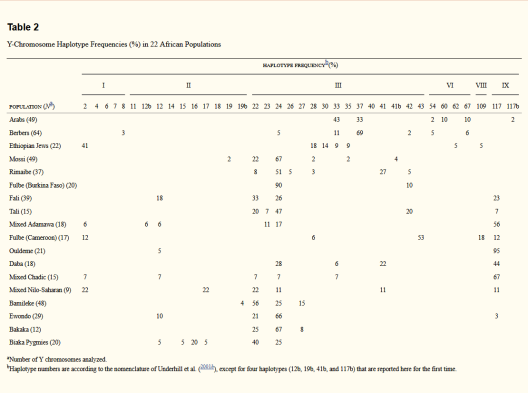

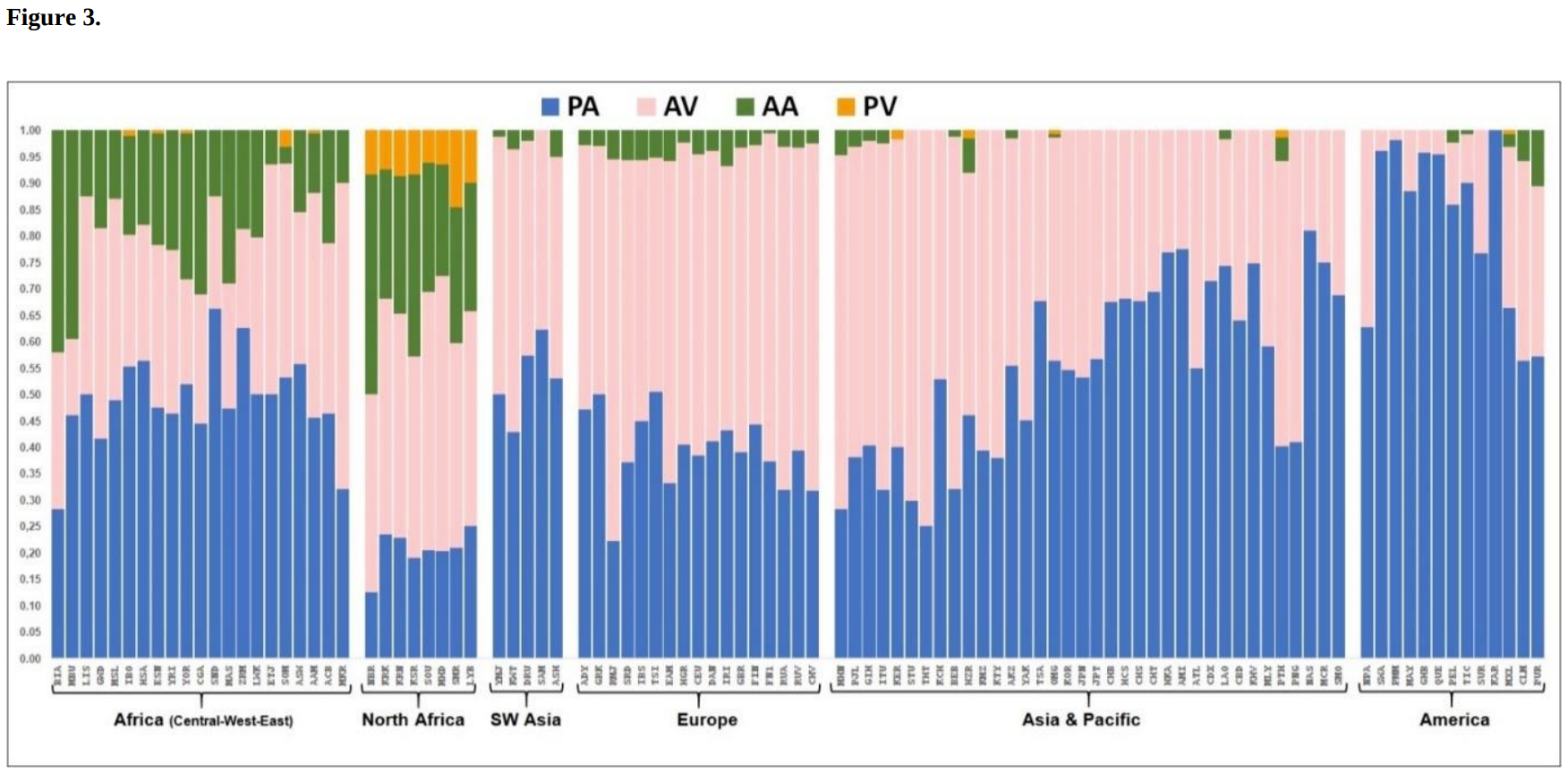

In Wang et al.’s Figure S1-B below, we can further see that this Kakapel 900BP sample primarily bears Nilo-Saharan/Niger-Congo-related ancestry (purple component), similar to that which defines the contemporary Dinka Nilote sample from Sudan. Kakapel 900BP thus seems to be the earliest appearance of a modern Dinka-like specimen in the archaeogenetic record. However, like the Dinka of today, Kakapel 900BP also bears a non-trivial amount of West Eurasian admixture (red component). This makes the sample an unsuitable proxy for inferring “pure” ancient Nilotic ancestry.

To find a less admixed Sub-Saharan African reference sample, we turn instead to the Kakapel 300BP sample from the same site. As with Kakapel 900BP, we note that the Kakapel 300BP cohort appears among the top eight ancient African specimens with whom the modern Nilote samples show the closest genetic ties on Vahaduo’s Distance parameter. We know that this affinity is due to shared ancient Nilotic ancestry rather than shared non-African admixture since, in Wang et al.’s Figure S1-B above, Kakapel 300BP carries only a small proportion of the West Eurasian red component, unlike both Kakapel 900BP and the Mota forager from Ethiopia (labeled Ethiopia_4500BP).

As an additional precaution, in order to ensure that Kakapel 300BP is indeed the most optimal source of “pure” Sub-Saharan African ancestry available, we will conduct a Vahaduo Multi analysis (process described below). We shall use the Kakapel 300BP sample as a Source population to infer ancient Nilo-Saharan ancestry in all of the contemporary Nilotic samples listed on the Global25_PCA_modern datasheet. Our resulting genetic model, displayed here, is successful; it produces plausible admixture levels for all of the examined Nilotic individuals and at acceptable Distance fits of <9%. By contrast, tests using other ancient Sub-Saharan African specimens, which have the highest levels of the Nilo-Saharan/Niger-Congo purple component above, are all failures. These experiments either grossly exaggerate the non-African admixture levels in the modern Nilotic samples and/or do not capture any Natufian admixture, which these specimens are known to possess (since they assimilated some Cushitic peoples, who bear such West Eurasian ancestry).

Finally, we will consult Wang et al.’s height data on the Kakapel 300BP sample (cf. Supplementary Material). Since the Sidamo and Sab, respectively, are both the most African-admixed and shortest of the Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations in Ethiopia and Somalia (see Ancient DNA from Ethiopia), this will enable us to determine whether the Kakapel 300BP specimen represents the main ancient Sub-Saharan African peoples whom the early Afro-Asiatic speakers in Northeast Africa absorbed. Kakapel 300BP, a young adult woman, is listed by Wang et al. at a diminutive stature of 156 cm or 5’1.5″, confirming that she likely does represent that ancient Sub-Saharan African contact population.

Step 2: Identify which Eurasian ancestries the modern Afro-Asiatic speakers of the Horn carry

Next, we will try and ascertain which specific Eurasian ancestries the Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking populations of the Horn region actually bear. To accomplish this, we will avail ourselves of the Vahaduo Admixture JS program’s Single tab and compare these modern samples (which are listed on the Global25_PCA_modern datasheet) with all 6000+ ancient Eurasian samples listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet. To this official G25 datasheet we shall add the coordinates for the newly-analysed EGY_1879BCE sample, which belong to the Middle Kingdom ancient Egyptian aristocrat Nakht-Ankh:

| EGY_1879BCE:Nakht-Ankh,0.0012,0.129,-0.044,-0.0965,-0.0031,-0.0534,-0.017,-0.0078,0.0551,-0.0049,0.0138,-0.0172,0.0306,-0.0015,0.0069,-0.0072,-0.0111,0.0053,-0.004,0.0042,-0.0012,0.0046,-0.0078,0.0026,-0.0013 |

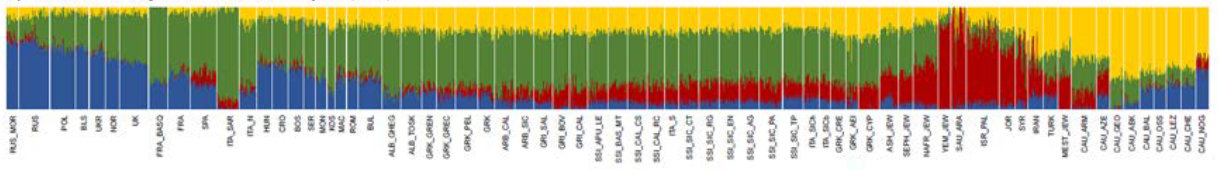

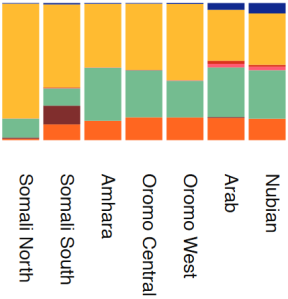

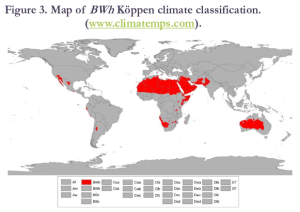

Before proceeding, we will also make sure to exclude any ancient samples that have non-trivial Sub-Saharan African admixture. The end result, shown below, has identified four principal non-African ancestries, three of which are West Eurasian (ancient Egyptian component, European-related Steppe component, and Levantine Natufian component) and one which is East Eurasian (East Asian component).

In order to verify our preliminary findings, we will again run Vahaduo’s Single analysis. However, now we shall include our “pure” early Nilotic sample (the Kakapel 300BP specimen) as a Source population alongside all of the ancient Eurasian populations from the Global25_PCA datasheet, while keeping our modern Afro-Asiatic-speaking individuals from the Horn as our Target populations.

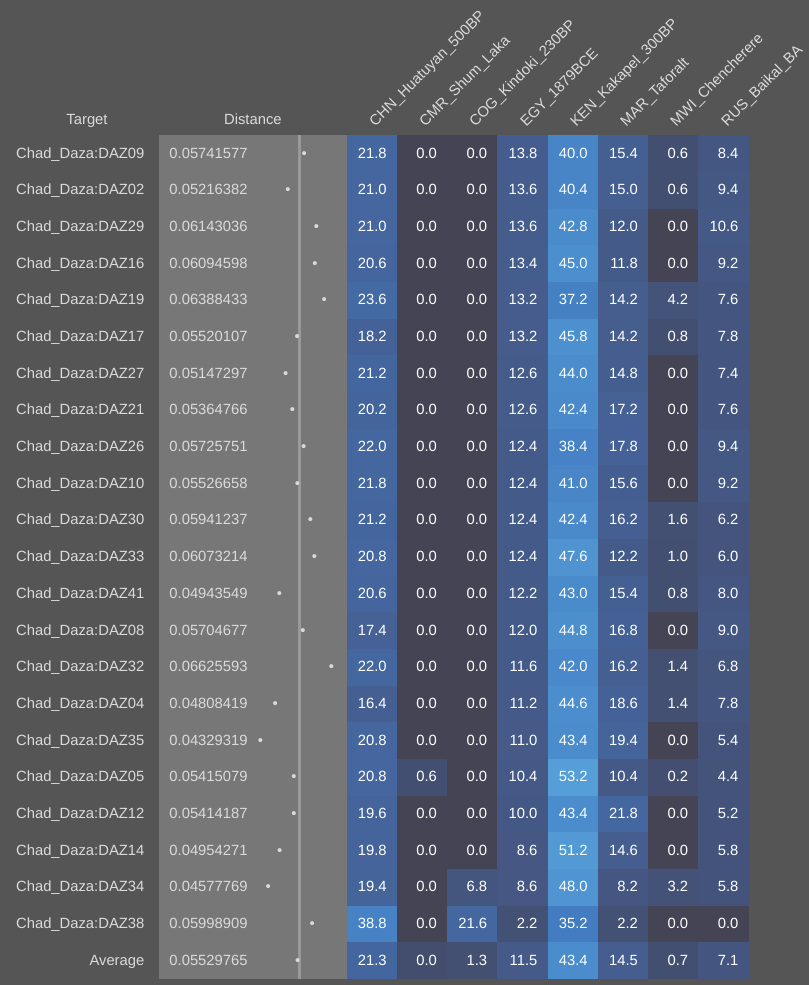

As an additional cautionary measure, we shall again conduct a Vahaduo Single analysis. Now we will add all of the other ancient Sub-Saharan African samples that have the least Eurasian admixture. These samples represent the “purest” Niger-Congo (COG_Kindoki_230BP:KIN002), East African Hunter-Gatherer (MWI_Chencherere:I4421_new_all), Pygmy (CMR_Shum_Laka:I10874_new_all), and Khoisan (ZAF_2000BP:bab001) specimens. Appending these samples will help us ascertain whether our Target Horn populations realistically carry any extra Sub-Saharan African admixture and from which sources.

As can be seen above, all of the aforementioned Eurasian ancestries appear once more, confirming their authenticity. Among the West Eurasian elements, the ancient Egyptian component is best represented by the EGY_1879BC sample, which is also the oldest Egyptian sample whose Global25 coordinates are available; the European-related Steppe component is best represented by the RUS_Baikal_BA specimens from Bronze Age Russia; and the Levantine Natufian component is best represented by the Levant_Natufian_EpiP specimens, which date to the Mesolithic. The East Eurasian element is best represented by the CHN_Huatuyan_500BP sample from late medieval China. We can also, for the first time, observe robust estimates of the actual ancestral proportions that characterize the Afro-Asiatic speakers analysed. On average, modern Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking individuals appear to carry over 70% Eurasian ancestry (most of which is West Eurasian, with a significant East Eurasian element), with around 25% Sub-Saharan African admixture (primarily derived from early Nilo-Saharan speakers like Kakapel_300BP, and secondarily derived from ancient East African Hunter-Gatherers like MWI_Chencherere) and under 5% Epipaleolithic North African ancestry (i.e. Iberomaurusian/Taforalt component).

Step 3: Quantify these ancestral proportions

To further break down the apportionment of these ancestral elements, we will now make use of the Vahaduo Admixture JS program’s Multi function. In order to efficiently interpret our findings, we shall utilize the five ancient Eurasian and two ancient Sub-Saharan African “best representative” samples, which we have just identified above. As expected, the end result (shown below) appears very similar to Vahaduo’s Single analysis:

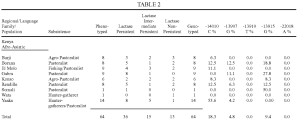

With regards to the table above, we may note that:

Tables of ancestral proportions for each Afro-Asiatic-speaking population (derived from the Vahaduo Admixture JS program’s Multi function):

Summary Vahaduo Multi table of the averages of each genome component for all the examined Horn populations:

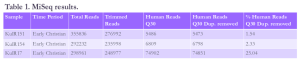

| Ancient East Asian (CHN_Huatuyan_500BP) | Ancient Pygmy (CMR_Shum_Laka) | Ancient Niger-Congo (COG_Kindoki_300BP) | Ancient Egyptian (EGY_1879BCE) | Iran Neolithic (Ganj_Dareh_N) | Ancient Nilo-Saharan (KEN_Kakapel_300BP) | Natufian (Levant_Natufian_EpiP) | Iberomaurusian (MAR_Taforalt) | East African Hunter-Gatherer (MWI_Chencherere) | European Steppe (RUS_Baikal_BA) | Anatolian Neolithic (TUR_Marmara_Barcin_N) | Ancient Khoisan (ZAF_2000BP) | Average non-African Ancestry | Average Sub-Saharan African Ancestry | Average Ancient North African Ancestry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afar (Ethiopia) | 23.9% | 0.8% | 0% | 18.2% | 0% | 14.4% | 24.3% | 0.9% | 5.5% | 12.1% | 0% | 0% | 78.4% | 20.7% | 0.9% |

| Agaw (Ethiopia) | 21.9% | 0.2% | 0% | 19% | 0% | 13.9% | 23.1% | 1.0% | 8.1% | 12.8% | 0% | 0% | 76.8% | 22.2% | 1.0% |

| Amhara (Ethiopia) | 22.2% | 0.2% | 0% | 18.1% | 0% | 14.7% | 24.9% | 1.0% | 7.7% | 11.3% | 0% | 0% | 76.4% | 22.6% | 1.0% |

| Eritrean | 20.4% | 1.1% | 0% | 16.7% | 0% | 16.7% | 30.0% | 0.2% | 4.5% | 10.3% | 0% | 0% | 77.5% | 22.3% | 0.2% |

| Ethiopian Jew | 22.6% | 0.3% | 0% | 17.6% | 0% | 15.1% | 26.4% | 0.3% | 7.5% | 10.3% | 0% | 0% | 76.8% | 22.9% | 0.3% |

| Iraqw (Tanzania) | 22.9% | 0% | 0% | 18.2% | 0% | 21.7% | 5.2% | 2.4% | 18.3% | 11.3% | 0% | 0% | 57.6% | 40.0% | 2.4% |

| Oromo (Ethiopia) | 22.9% | 0.1% | 0% | 17.2% | 0% | 17.6% | 19.4% | 0.8% | 11.6% | 10.4% | 0% | 0% | 69.9% | 29.3% | 0.8% |

| Rendille (Kenya) | 25.6% | 0% | 0% | 18.1% | 0% | 25.7% | 10.7% | 1.8% | 9.6% | 8.5% | 0% | 0% | 62.9% | 35.3% | 1.8% |

| Somali (Kenya) | 23.6% | 0.2 | 0% | 18.5% | 0% | 20.4% | 14.1% | 2.1% | 9.1% | 12.1% | 0% | 0% | 68.2% | 29.7% | 2.1% |

| Somali (South Somalia) | 23.6% | 0% | 0% | 19.3% | 0% | 20.0% | 13.3% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 13.1% | 0% | 0% | 69.3% | 27.7% | 3.0% |

| Tigray (Ethiopia) | 21.7% | 0.1% | 0% | 17.8% | 0% | 15.5% | 26.3% | 0.8% | 6.4% | 11.5% | 0% | 0% | 77.2% | 22.0% | 0.8% |

| Wolayta (Ethiopia) | 21.7% | 0.9% | 0% | 16.8% | 0% | 17.5% | 15.6% | 1.8% | 14.7% | 10.9% | 0% | 0% | 65.1% | 33.1% | 1.8% |

Step 4: Corroborate these findings with other scientific evidence

As a fourth step in our analysis, we shall further establish the veracity of our findings by corroborating them with other scientific evidence gathered from different disciplines. We will focus on the Steppe element because the ancient Egyptian component is fully discussed on Punt: an ancient civilization rediscovered.

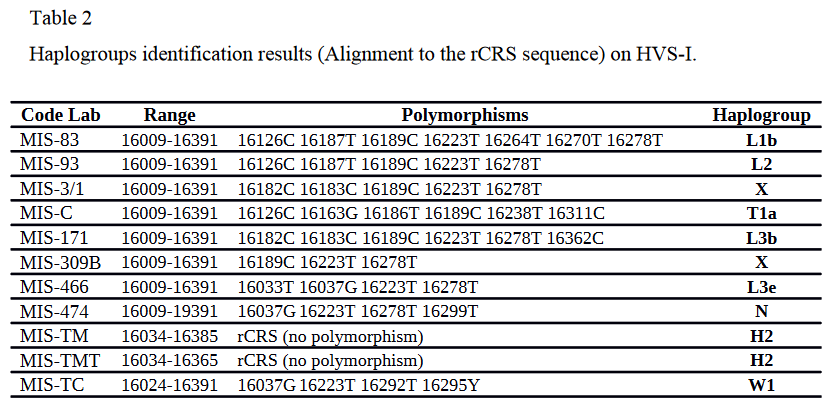

In regards to the European-related Steppe ancestry, which we have just identified above, uniparental markers (both Y-DNA and mtDNA) support the existence of such an influence in Northeast Africa. Gad et al. (2020) report that the 18th Dynasty ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III, his son Pharaoh Akhenaten and his grandson Pharaoh Tutankhamun, who governed from the Amarna site in Upper Egypt, belong to the Y-DNA haplogroup R1b (cf. Gad et al. (2020a); Gad et al. (2020b)). iGENEA further specifies that these Amarna royals fall under the clade’s M269 branch, the most common paternal lineage carried today by European males. Yatsishina et al. (2021) likewise divulge that one of the ancient Egyptian mummies they analysed at the Kurchatov Institute bears the R1b-M269 haplogroup. Maternally, Khairat et al. (2013) state that a mummified ancient Egyptian individual they studied belongs to the I2 mtDNA haplogroup. This mitochondrial lineage has been detected among various early Steppe cultures of Europe. It is nowadays quite rare (typically under 5%), attaining a global frequency peak of 23% among Cushitic-speaking remnant groups in the Great Lakes region (Castrì et al. (2008)). Moreover, the basal I* haplogroup has only been observed among three persons worldwide; two of these individuals are from Somalia and the other is from Iran (Olivieri (2013)). White et al. (2023) also detected the rare H4a1 mtDNA clade in the mummy of Takabuti, an ancient Egyptian noblewoman from Thebes, Upper Egypt. The scientists note that this maternal lineage has been “described in antiquity only in Central Europe,” and propose that the haplogroup is “suggestive of the introduction of new gene pools during the Late Period of ancient Egyptian history.”

Y-DNA haplogroups of the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III, his son Pharaoh Akhenaten, and his grandson Pharaoh Tutankhamun, who ruled from the Amarna site in Upper Egypt. These 18th Dynasty kings belong to the R1b clade, which today is the most common paternal lineage borne by Europeans. This finding supports an ancient presence in the Nile Valley of peoples bearing European-related Steppe ancestry (Gad et al. (2020a)).

Autosomal DNA analysis of the Amarna kings has also unveiled a clear Steppe-related ancestral affinity. Hawass et al. (2010) typed these ancient Egyptian monarchs for short tandem repeats (STRs or microsatellites). The genetic testing company DNA Tribes then compared these specimens’ microsatellite markers against those belonging to various modern populations contained within its internal database. It reported that these specimens showed greatest genetic affinity with the autosomal STR profiles of contemporary Sub-Saharan African individuals. However, this conclusion is rendered doubtful by the relatively small size of DNA Tribes’ internal reference population database. Using the PopAffiliator autosomal STR prediction software (which is now defunct), Gourdine et al. (2018) similarly asserted that these Amarna mummies had a greater probability of assignment to PopAffiliator’s “Sub-Saharan Africa” cluster (41.7%-93.9%) than to its “Eurasia” (3%-41.5%) or “Asia” (0.3%-16.7%) clusters. However, a glance at PopAffiliator’s STR Worldwide Database, where it lists the reference populations against which it compared the Amarna specimens’ microsatellites, reveals that these comparison samples were few in number, consisting of just 80 populations in total. PopAffiliator, moreover, included a sample from Somalia among its four reference populations from Sub-Saharan Africa. This had the effect of biasing and invalidating its microsatellite assignments because autosomal STR analysis of ethnic Somalis has found that these Cushitic-speaking individuals actually possess considerable Eurasian affinities (Steele et al. (2014), the largest global autosomal STR analysis, groups its Somalia sample within its IC6 Middle East cluster). Y-DNA (Trombetta et al. (2015), Supplementary Table 7)), mtDNA (Stevanovitch et al. (2004)), and autosomal DNA (Hodgson et al. (2014), Supplementary Text S1; Dobon et al. (2015); Almarri et al. (2021), Table S4) analyses likewise indicate that Somalis and other Afro-Asiatic speakers from the Horn share close ties with both ancient and modern Egyptians. Altogether, this explains why PopAffiliator clustered the Amarna mummies as it did: the specimens were showing affinity with the Somalia reference sample, specifically.

Furthermore, a cross-analysis of the Amarna royals’ autosomal STRs with the microsatellites listed on the more extensive Allele Frequency Database (ALFRED) — which includes well over 400 different worldwide populations, including many understudied South Asian groups — demonstrates instead a close affiliation with populations in South Asia and Europe (see our study Autosomal STR Analysis of the Ancient Egyptian Amarna Royal Family, Pharaoh Ramesses III, and Unknown Man E (Prince Pentawere). We know that this affinity is specifically tied to ancient Steppe-bearing peoples because the alleles with a primary South Asian affiliation also often include among their top results ALFRED’s eastern European samples, and eastern Europe is where the Steppe component is believed to have ultimately originated (e.g. 22.50% of Croatians carry the Pharaoh Akhenaten’s FGA=23 allele, which peaks at 40% in a Reddy/Vanne sample from South Asia). The reverse is also true. That is, the alleles with a primary European affiliation likewise frequently include South Asian groups among their top results (e.g. 48% of the Drokpa in South Asia carry the courtier Thuya’s D7S820=10 allele, which peaks at 52.60% in a Croatian sample). This finding agrees with our Vahaduo Admixture JS analysis, as well as with the Steppe-associated uniparental markers that these ancient Egyptians carry.

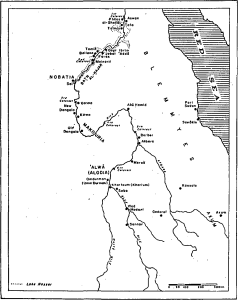

What’s more, analysis of limb proportions is suggestive of contact with populations inhabiting the temperate zone. Holliday (2013) examined various old and recent global samples, including an ancient Egyptian cohort (dating from the Predynastic to Middle Kingdom), a Kerma sample (dating from the Middle Kingdom i.e., the same time period as the Global25 sample EGY_1879BCE, which belongs to Nakht-Ankh), and a Christian-era Nubian sample (dating from the 4th to 7th centuries CE). He reports that his Middle Ages Nubian cohort had a more cold-adapted body plan, similar to his medieval European samples. On the other hand, Holliday’s ancient Egyptian cohort and Kerma sample had more linear, tropically-adapted limbs, similar to the “leptosome tendency” which Coon (1939) affirms is typical of Bedouin Hadhramis in southern Arabia. This is consistent with our analysis below, which indicates that the Christian period inhabitants of Kulubnarti in Nubia bore some Steppe-related admixture. It therefore appears that during Nakht-Ankh’s lifetime, Steppe ancestry, although already present since the Neolithic period, had not yet spread throughout the Nile Valley.

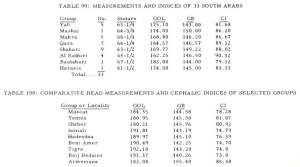

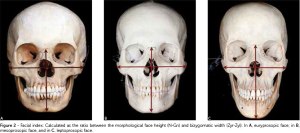

The cephalic indices (CI) of the ancient Egyptian Amarna monarchs also attest to a European Steppe affiliation. Kemp and Zink (2012) report that, with the exception of the courtier Yuya, who is markedly dolichocephalic (long-headed, with a CI of 70.3), all of these royal mummies are either mesocephalic (medium-headed) or brachycephalic (broad-headed). That is, they possess cephalic index values of 75 or greater. Akhenaten and Tutankhamun are, in fact, brachycephalic, with high cephalic indices of 81.0 and 83.9, respectively. This is atypical for both ancient and modern Egyptians, who for the most part tend toward dolichocephaly (cephalic indices under 75). However, brachycephaly is common in eastern Europe, where frequencies of the Steppe ancestral component are today maximized (cf. Godina (2011)).

Additionally, philological evidence backs a Steppe connection. For example, Bahadur (1917) notes that “Eusebius states that Ethiopians [Meroites] emigrating from the River Indus settled in the vicinity of Egypt [Meroe].” Nilus similarly relayed to Apollonius Tynaeus that “the Indi are the wisest of all mankind. The Ethiopians [Meroites] are a colony from them: and they inherit the wisdom of their forefathers.” The Indus river mostly traverses Pakistan, an area that historically was settled by Indo-European speakers, who carried Steppe ancestry.

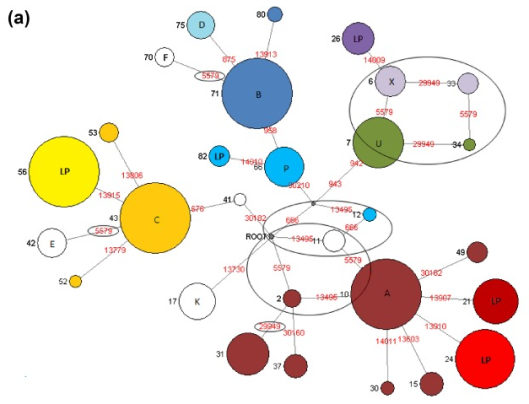

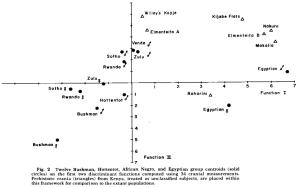

Craniometric analysis likewise points to a close association between Afro-Asiatic speakers in Northeast Africa, Indo-European-speaking and Dravidian-speaking populations of South Asia, and Europeans. This affinity extends back in time to subsume early groups in these areas, including the ancient Egyptians and post-Neolithic Nubians. Brace (1993), for instance, asserts that “insofar as India has metric ties with any other populations, it combines with Nubia [Bronze Age/X-Group and Medieval/Christian Era samples] and then the Somalis to join Europe and the Egyptians [Predynastic and Late Dynastic samples] as a last link before that set of branches ties in with the rest of the world.” Multiple other studies have also observed a similar affiliation (e.g. Morton (1854), Stoessiger (1927), Coon (1939), Sergent (1997), Brace et al. (2006)). This aligns well with a diffusion of ancient Steppe-bearing peoples into Northeast Africa and South Asia, either indirectly from a common waypoint near Central Asia or directly from Europe.

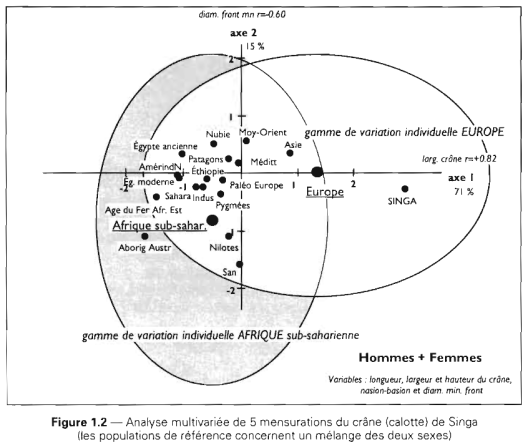

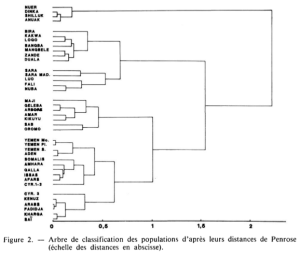

Craniometric analysis of ancient and contemporary global populations. The modern Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations in Northeast Africa, the ancient Egyptians, the Bronze Age Nubians (X-Group) and Medieval Nubians (Christian period), modern Indo-European-speaking and Dravidian-speaking groups of India, and modern and ancient Europeans cluster together. This is consistent with a spread of Steppe-bearing peoples from Europe to these areas, either directly or indirectly via Central Asia (Brace (1993)).

Furthermore, hair morphology supports an early European-associated presence in Northeast Africa. Lazaridis et al. (2022) conducted a comprehensive analysis of phenotypic traits borne by ancient individuals exhumed in Europe and Asia. The scientists indicate that blond hair was most common among their ancient European specimens and that red hair was exclusively found among these samples. This is key since Brothwell and Spearman (1963), employing reflectance spectrophotometry, observed a number of authentically blond ancient Egyptian individuals; their hair samples were not affected by either hair dye or cuticular damage. Strikingly, Griggs (1988) reports that excavations he led at a Roman-Christian era cemetery in Seila, located in the Fayum region of Egypt, yielded the remains of many individuals with blond or red hair. He affirms that “of the 37 adults whose hair was still preserved[…] there were 4 redheads, 16 blondes, 12 with light or medium brown hair, and only 5 with dark brown or black hair. Of those whose hair was preserved 54% were blondes or redheads, and the percentage grows to 87% when light-brown hair color is added.” Similarly, Janssen (1978) writes that “330 graves were excavated in cemetery 221 (Meroitic) and a proportion of blond individuals of Caucasoid type found.” Hrdy (1978), also analysing Meroitic remains, notes that many ancient individuals buried at Semna South in Sudanese Nubia had blond or red hair. He suggests that this “probably points to a significantly lighter-haired population than is now present in the Nubian region.”

Correspondingly, several of the ancient Egyptian mummies belonging to the Amarna royal lineage, including the aristocrats Yuya, Thuya and Tiye as well as the Pharaoh Ramesses III, also have blond or red hair. These are the same monarchs who, as we have just seen, carry some European-affiliated autosomal STR markers. In the case of Yuya, Hawass and Saleem (2016) argue that his blondism was caused by either the fading of henna dye on white hair or the interaction of embalming materials and applied henna. However, the Egyptologist Janet Davey of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine later demonstrated through laboratory experimentation that natron used in the mummification process has no effect on hair color, regardless of whether or not a specimen’s hair had been dyed with henna during embalming. This finding was confirmed by a followup microscopic analysis conducted by Gale Spring of RMIT (cf. Smith (2016)). Hamed and Maher (2021), using various analytical processes (viz. microscopic examination, FTIR spectroscopy, gas chromatography and raman spectroscopy), also observed that Yuya’s natural hair color is indeed a reddish-blond. Elemental analysis of his hair shafts showed a high concentration of sulphur, an element that occurs in greater quantities in blond or red hair than in black hair. Tiye and the other royal mummies likewise reportedly have naturally red or blond hair. What’s more, a tomb painting of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III depicts him with a light reddish mane. This altogether underlines the fact that blond and red hair were prevalent among the ancient Egyptian Amarna nobles.

In summary, the existence of an old European Steppe ancestral component in Northeast Africa, analogous to that which we have detected through our Vahaduo Admixture JS genome analysis, is supported by studies on the Amarna royal family. These ancient Egyptian monarchs ruled from the Amarna site in Upper Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. Their mummies have been found to bear Steppe-related autosomal STR markers, Steppe-related uniparental haplogroups (notably, the R1b Y-DNA clade and the I mtDNA clade), primarily mesocephalic or brachycephalic skulls, and blond or red hair, much like populations in eastern Europe where the Steppe component originally dispersed from. Moreover, craniometric examination of modern Afro-Asiatic speakers and Nubians in Northeast Africa reveals close ties with groups in South Asia and Europe, consistent with population movements from the European Steppe into Central Asia and from there into both the Nile Valley/Horn and the Indian subcontinent. Such early migrations are also backed by ancient texts, which assert that peoples from the Indus river vicinity settled near Egypt, in the Meroë area situated in present-day Sudan.

Step 5: Confirm whether the ancient Pastoral Neolithic and Kulubnarti specimens share this ancestral composition

Fifthly, we shall explore if the ancient Cushitic settlers of the Pastoral Neolithic and the Christian-era Kulubnarti specimens from Nubia carry these same ancestral components and at similar frequencies. This will help us determine whether the Eurasian elements, which we have just identified, are legitimate ancestries or mere statistical constructs. It will also give us some insight as to which of these components are the original ancestries of the Afro-Asiatic speakers and which components are instead intrusive (i.e., elements acquired later through interbreeding).

We start off by launching another Vahaduo Single run, this time using the Pastoral Neolithic samples as our Target populations. The “pure” ancient Sub-Saharan African specimens (Kakapel_300BP, MWI_Chencherere, COG_Kindoki), CMR_Shum_Laka, ZAF_2000BP) and the 6000+ ancient Eurasian specimens listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet will once more serve as our Source populations. The end result is displayed below. It again primarily shows the same assortment of West Eurasian (viz. ancient Egyptian, Steppe and Natufian components) and East Eurasian (East Asian component) ancestries, which occur at similar total frequencies as before (over 70%). The remaining minority of the Pastoral Neolithic individuals’ ancestral composition consists of Sub-Saharan African admixture (~25%) and North African Iberomaurusian admixture (under 5%), just like the modern Afro-Asiatic speakers from the Horn region.

When we repeat this process for the Kulubnarti samples, we encounter the same ancestral components occurring again at practically identical percentages. However, one key difference between the Kulubnarti individuals on the one hand, and the Pastoral Neolithic and modern Horn samples on the other, is that the Kulubnarti specimens have little East African Hunter-Gatherer admixture. Almost all of their ancient Sub-Saharan African admixture instead consists of the Nilo-Saharan Kakapel300BP element.

Lastly, when we run a Vahaduo Multi analysis on both our Pastoral Neolithic and Kulubnarti ancient samples, here too we come away with similar ancestral components and at comparable percentages:

With regards to the Pastoral Neolithic table above, we may note that:

Tables of ancestral proportions for each Pastoral Neolithic group:

Step 6: Confirm whether modern Egyptians share this ancestral composition

Sixthly, we will examine whether contemporary Egyptian individuals have the same ancestral makeup as just outlined. As our Target population on Vahaduo Admixture JS, we shall use the Egyptian samples listed on Eurogenes’ official Global25_PCA_modern datasheet. For our Source populations, we will again utilize the Eurasian samples on the Global25_PCA datasheet, alongside the five “pure” ancient Sub-Saharan African representatives. With our Target and Source populations now loaded, we will tap into Vahaduo’s Single function, letting the program sift through Global25’s massive 6000+ samples to pinpoint for us the most optimal sources of ancient Eurasian ancestry.

From the above, it is apparent that modern Muslim Egyptians (i.e. non-Coptic Egyptians) do generally share the same ancestral composition as the Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations in the Horn of Africa. West Eurasian elements (ancient Egyptian, European-related Steppe, and Levantine Natufian components) and an East Eurasian element (East Asian component) are most prominent here too, and minor Sub-Saharan African admixture and a minute North African Iberomaurusian admixture can again be detected. That said, many of the analysed Muslim Egyptian individuals also show an affinity with the contemporary Levant/Arabia, as exemplified by the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity component. This West Eurasian ancestral element — which mainly consists of Natufian ancestry, with some later acquired Anatolian Neolithic and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherer/Iran Neolithic admixtures — is most typical of modern Arabic speakers, as well as many Yemeni Jews and some Mahra individuals (see Vahaduo Single analysis here).

Like before, to re-confirm the main ancestries that we have just identified and organize them into table format for easier interpretation, we will end with a Vahaduo Multi analysis. We shall include the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity sample to capture the modern Arabian admixture that is present in Egyptians. Next, we shall re-run our Multi analysis and include G25’s TUR_Marmara_Barcin_N and IRN_Ganj_Dareh_N samples among our Source populations so as to account for, respectively, the Anatolian Neolithic and Iran Neolithic elements that are inherent in the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity component:

As can be seen in the tables above, the Muslim Egyptian individuals still bear the same ancestries as other Afro-Asiatic speakers in the Horn of Africa and at comparable frequencies, confirming the observed affinities. On average, modern Egyptians carry around 84% non-African ancestry, the majority of which consists of West Eurasian elements (viz. primarily ancient Egyptian, Steppe and Natufian components, as well as some extra Anatolian Neolithic and Iran Neolithic admixtures) and a minority of which comprises an East Eurasian element (East Asian component). Furthermore, they also harbor around 13% Sub-Saharan African admixture (primarily consisting of the Nilo-Saharan element, and secondarily of the Niger-Congo element) and a very minor North African Iberomaurusian admixture (3%).

Coptic Egyptians are not yet included on the official Global25 datasheets, but they seem to have a somewhat different ancestral composition. This is suggested by the Coptic samples on IllustrativeDNA, a service which uses G25 technology to process its own coordinates (not official Global25 coordinates). When these coordinates are run through Vahaduo Admixture JS’s Single function, the Coptic individuals appear to derive over 99% of their ancestry from the EGY_1879BCE ancient Egyptian sample. However, since IllustrativeDNA’s samples are often low coverage, producing bloated fits on Vahaduo’s Distance parameter of >15%, they frequently do not allow for precise identification of all the ancestral components an individual might bear nor can they accurately quantify those elements (e.g. when used as Target populations against Global25’s ancient Eurasian Source populations, IllustrativeDNA’s Afro-Asiatic-speaking samples from the Horn have Vahaduo Distance fits which are around three times higher than Eurogenes’ official Global25 Horn samples; compare this with this). We must therefore perform an additional Vahaduo Distance analysis on our Coptic samples to make sure that they are reliable. When this is done, our Copts and other Egyptian samples from IllustrativeDNA wind up showing almost identical Distance fits as Eurogenes’ official Global25 Egyptian samples (see here and here).

This confirms that Coptic Egyptians indeed descend directly from Egyptians dating from at least the earlier Dynastic period — something which was already strongly implied by their traditional language, Coptic, a later iteration of the ancient Egyptian tongue. As such, Coptic Egyptians seem to have been largely unaffected by the aforementioned gene flow into the Nile Valley, which we have detected in both the ancestral Cushites of the Pastoral Neolithic and the later Dynastic period Egyptians. Having said that, besides the Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1b common among Afro-Asiatic speakers, some modern Coptic individuals also bear the R1b and J paternal clades (E1b1=74% and J1=1% among Copts in Upper Egypt according to Crubézy et al. 2010; E1b1b=21%, J=45% and R1b=15% among Copts in Sudan according to Hassan et al. (2008)). The R1b and J lineages were first brought to the Egypt area by newcomers bearing, respectively, European-related Steppe ancestry (seemingly introduced as early as the Neolithic) and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherer/Iran Neolithic ancestry (introduced during the later Dynastic period). Hence, there is genetic evidence of contact between Coptic Egyptians and foreigners. Our Vahaduo Single analysis below, however, demonstrates that this gene flow was ultimately also of negligible importance because, unlike Muslim Egyptians, Copts (both in Sudan and Egypt) for the most part do not bear these ancestral components.

We will finish by conducting a Vahaduo Multi analysis on all of the Coptic and Egyptian samples discussed above. To these we shall add Hollfelder et al. (2017)’s Coptic sample, as well as that paper’s Nubian cohort and other Sudanese Afro-Asiatic-speaking groups. The resulting data table, shown below, indicates that Hollfelder et al.’s samples, including their Coptic representative, are unreliable since they have the tell-tale inordinately high Distance fits (on average >15%; one Sudanese “Arab” Shaigia sample has an absurd Distance fit of 47%), few identified ancestral elements (usually 2 to 3 maximum), and skewed component frequencies typical of low coverage samples. However, it is interesting to note that the Egyptian samples from Cairo and Mansoura share an almost identical genetic profile as Coptic Egyptians, albeit with a small Sub-Saharan African admixture. Both of these samples are from IllustrativeDNA and have acceptable Distance fits of <9%. Since Cairo and Mansoura are cities located in northern Egypt, where the EGY_1879BCE specimen was excavated from at Deir Rifeh, we therefore now have, for the first time, genetic evidence substantiating the existence of Upper Egyptian/southern Egyptian and Lower Egyptian/northern Egyptian types.

Anthropologists have long observed such a cleavage in the Nile Valley’s skeletal record. For example, Batrawi (1946) remarks that the ancient Egyptians appeared to have been divided into two distinct but related physiognomies, and that “the study of the available measurements of the living, however, apparently suggests that the modern population all over Egypt conforms more closely to the southern type” (also see G. Billy (1975)). We can now state that the primary distinguishing factor between these two osteological types seems to have been gene flow from the European Steppe and later also from the Arabian peninsula rather than Sub-Saharan African admixture. This is because the contemporary Egyptian samples from Global25 and the northern Egyptian samples from IllustrativeDNA have almost the same low level of Sub-Saharan African admixture (13% and 11%, respectively). Ergo, after the early Dynastic period, foreign influences from Europe and Asia significantly impacted northern Sudan and southern Egypt as compared to northern Egypt.

Step 7: Confirm whether modern Sudanese “Arabs” also share this ancestral composition

For the seventh step in our analysis, we shall inquire whether Sudanese “Arabs” share the same ancestral composition as the Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking populations of the Horn of Africa. We will follow the exact same procedure as just described above for Egyptians, using Kababish as our Sudanese “Arab” cohort. To these we shall add two other samples from Sudan, of Rashaayda Arabs and Baggara “Arabs.” In addition, we will examine Daza (Gorane or southern Toubou) individuals and other Baggara “Arabs,” both from Chad. All of these samples were originally published in Fortes Lima et al. (2022) and later converted to Global25 coordinates for use in the Vahaduo Admixture JS software program (see here for the unscaled or raw G25 coordinates; though not official Global25 samples, they are high coverage/decent quality).

Our resulting Vahaduo Single analysis is as follows:

Judging by the Single analysis above, it is apparent that the Kababish “Arabs” generally bear the same ancestral makeup as the Horn’s Afro-Asiatic speakers.

To better organize our thoughts and strengthen our interpretation, we will finish by conducting a Vahaduo Multi analysis:

From the data table above, it is clear that the Kababish “Arabs” of Sudan do have the same overall ancestral composition as the Afro-Asiatic speakers from the Horn of Africa. The Kababish individuals bear a predominant Eurasian ancestry (averaging almost 70%), comprising majority West Eurasian elements (ancient Egyptian, European Steppe, and Levantine Natufian components) and a minority East Eurasian element (East Asian component). Furthermore, these individuals carry some Sub-Saharan African admixture (close to 30%) and a trace Iberomaurusian admixture (under 1%). One characteristic difference, however, is that the Kababish’s Sub-Saharan African admixture almost entirely consists of the “pure” ancient Nilo-Saharan component (KEN_Kakapel_300BP). Their comparatively trivial frequencies of the East African Hunter-Gatherer component (MWI_Chencherere), averaging just 1%, are instead more congruent with our modern Egyptian and ancient Kulubnarti results above, as well as our results for contemporary Libyans below. All of these samples have negligible frequencies of this forager element, which emphasizes that this component is indeed autochthonous to eastern Africa rather than the Nile Valley.

For their part, the Baggara “Arab” samples from Sudan and Chad are very similar to the Sudanese Kababish “Arab” cohort. These populations, in fact, appear to be of the same origin. However, it is evident from the figures above that the Baggara have intermixed more with their Nilo-Saharan-speaking neighbors since they harbor greater average percentages of the KEN_Kakapel_300BP component (40.2% for the Baggara in Chad and 47.3% for the Baggara in Sudan).

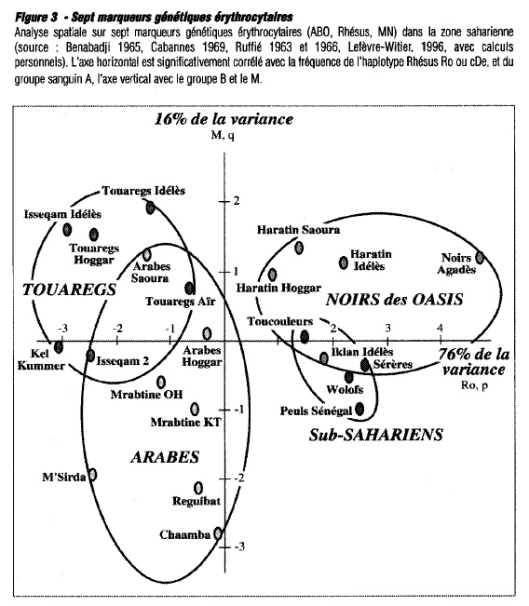

The samples belonging to the Daza (Gorane), or southern Toubou, are almost identical to those of the Baggara “Arabs.” Just one key difference separates these two groups, and that is the Daza’s appreciable frequencies of the North African Iberomaurusian component (averaging 14.5%). In this respect, the Daza individuals appear more similar to the modern Libyans (discussed below), who have a comparable average percentage of this Taforalt element. It may be that the Daza and Teda or northern Toubou — as hypothesized successors of the ancient Garamantes/Garamantians, whose old territory they currently occupy — were originally Afro-Asiatic speakers of Libyan stock. Hence, as Kirwan (1934) observes, the etymological connection between the ethnonyms Goran and Garamantes. However, since the Daza and other Toubou intermingled significantly with their Nilo-Saharan neighbours, it is conceivable that they eventually adopted the latter’s language. This ultimately would have served to obscure their Berber origins.

The Rashaayda Arabs (Rashaida) of Sudan and Eritrea are relative newcomers to Northeast Africa. Their arrival from the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia during the 19th century is well-documented. It is, therefore, completely expected that they should mostly bear Natufian-related ancestry. Nevertheless, just to confirm that these individuals are indeed of peninsular Arab origin, we shall run a final Vahaduo Multi analysis with all of our other Sudanese and Chadian “Arab” samples, but this time include the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity cohort to capture any such recent ancestry. We will also include the TUR_Marmara_Barcin_N and IRN_Ganj_Dareh_N specimens to see if our Rashaayda individuals and other samples carry any extra Anatolian Neolithic and Iran Neolithic admixture, respectively. The resulting analytical table below shows that, unlike the Kababish “Arab”, Baggara “Arab” and Daza Toubou samples, the Rashaayda Arabs clearly are of recent peninsular Arab origin. They are the only Arabic-speaking population of Sudan and Chad in our dataset that mostly belongs to the associated Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity component (68.6% on average). Among the Kababish and Baggara, Arabian admixture is instead restricted to a handful of individuals (notably, the Chadian Baggara individual ABA032, who has an elevated 41.4% frequency of the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity element). These outliers are likely descendants of peninsular Arab Muslims, who introduced the Islamic faith and the Arabic language to the Sudan area during the medieval period.

Tables of ancestral proportions for each Arabic-speaking Sudanese and Chadian group as well as the Daza Toubou:

Step 8: Confirm whether modern Maghrebis also share this ancestral composition

As an eighth step in our analysis, we shall explore whether contemporary Afro-Asiatic speakers of the Maghreb region in northwestern Africa also share the ancestral composition described above. We will begin, as previously, by conducting a Vahaduo Distance test on all of Global25’s ancient African samples that possess the least Eurasian admixture. This should help us determine which population mainly contributed the Sub-Saharan African admixture that modern Maghrebis carry.

Of the top eight results listed above, the Congo Kindoki specimens are the most suitable Niger-Congo proxies for our Maghrebi samples. This is because, along with the Congo NgongoMbata 220BP cohort, they are the “purest” available ancient specimens bearing Niger-Congo-related ancestry (see Step #9 below on how we know that), and Bekada et al. (2015) have found that contemporary Maghrebis harbor such Yoruba-like admixture. However, since the COG_Kindoki_230BP:KIN004 sample belongs to the Indo-European-associated Y-DNA haplogroup R1b1 (cf. Wang et al. (2020), Table S10), we shall avoid using it. We will instead utilize COG_Kindoki_230BP:KIN002 as our reference sample, for it bears the E1b1a paternal clade common among modern Niger-Congo speakers.

Moving forward, we shall now perform a Vahaduo Single analysis on our Maghrebi samples. The non-African specimens listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet will, alongside Congo_Kindoki and the other “pure” ancient Sub-Saharan African samples, again serve as our Source populations. Such a test leverages Vahaduo Admixture JS’s processing capabilities, allowing the program to find for us the exact ancestries our Target populations carry.

From the above, we can see that Maghrebis do generally share a similar ancestral makeup as other Afro-Asiatic speakers in the Horn and Nile Valley. Here too we may note the now-familiar array of majority West Eurasian elements (ancient Egyptian, European-related Steppe, and Levantine Natufian components) and a minority East Eurasian element (East Asian component), with a low Sub-Saharan African admixture (primarily derived here from the ancient Niger-Congo sample Congo Kindoki 230BP, with ancillary gene flow from the ancient Nilo-Saharan sample Kakapel 300BP). However, a major difference between these populations is that the Iberomaurusian/Taforalt component forms a large portion of the ancestry of virtually all modern Maghrebi individuals, whereas this element is found at very low frequencies toward the east (typically under 5%). Anatolian Neolithic-related ancestry (represented by TUR_Marmara_Barcin_N) is also an important admixture element, particularly among coastal populations in the north, with Iran Neolithic-related admixture (represented by IRN_Ganj_Dareh_N) also present. Furthermore, one population, the Arabic-speaking Rbaya of Tunisia, seems to be descended from recent settlers from the Arabian peninsula rather than Arabized Berbers. These Rbaya individuals carry a predominant Natufian ancestry like many peninsular Arabs, and (notwithstanding Sub-Saharan African admixture) low percentages of said quintessential Maghrebi ancestral elements.

To better marshal the findings above and more easily observe the identified trends via table format, we shall conclude by running a Vahaduo Multi analysis on our Maghrebi Target populations:

Fregel et al. (2018) studied Late Neolithic individuals excavated at the Kelif el-Boroud site in Morocco, and report that these ancient specimens bore ancestry comprised of roughly equal Natufian and Anatolian Neolithic genome elements. Given this discovery, we must conduct a Vahaduo Multi test using Global25’s MAR_LN ancient sample as an additional Source population. This will help us determine whether the Anatolian Neolithic ancestry, which we have just observed above in our Maghrebi samples, was primarily 1) inherited from these Late Neolithic Moroccans, or 2) acquired later through absorption of peoples arriving from southern Europe or western Asia. From the data table below, it is apparent that scenario #2 is correct; most Maghrebi groups did not derive their Anatolian Neolithic admixture from the Late Neolithic specimens from Kelif el-Boroud. Contemporary Maghrebi individuals carry the MAR_LN component at a low average of 4.4%, with little change in average frequencies of the Anatolian Neolithic-related TUR_Marmara_Barcin_N component (23.4% vs. 25.8%). This is also evidenced by the fact that haplogroup T, the only paternal clade that Fregel et al. observed among their Late Neolithic Moroccan specimens, is rare among just about all modern Maghrebi groups. The latter populations instead largely belong to the E1b1b lineage, as do most Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusians, Mesolithic Natufians, Pre-Pottery Neolithic makers, Early Neolithic specimens exhumed from the Ifri n’Amr or Moussa site in Morocco, ancient Cushites of the Pastoral Neolithic, and ancient Egyptian individuals.

When Libyans are added to our Maghrebi dataset, they appear most similar to Muslim Egyptians inhabiting the Nile Valley; they also share appreciable ties with the Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking populations of the Horn. The Libyan individuals have the same basic ancestral makeup as these Muslim Afro-Asiatic speakers to their immediate east, carrying majority West Eurasian ancestries (viz. ancient Egyptian, European-related Steppe, and Natufian components) and a minority East Eurasian ancestry (East Asian component), as well as a bit of Sub-Saharan African admixture and a small North African Iberomaurusian/Taforalt admixture. However, Libyans (13.5%) have a higher average frequency of the Iberomaurusian component than Egyptians (2.9% among Muslims, 0% among Copts) and Horn populations (1.2%), though significantly lower than Maghrebis (28.5%). Like Muslim Egyptians and to a lesser extent Maghrebi groups, Libyans also sustained recent gene flow from the Arabian peninsula. This is evidenced by the presence of the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity component in our Libyan dataset, an ancestral element which again is typical of modern Arabic speakers.

Step 9: Repeat analytical steps above with a control population to ensure accuracy and replicability

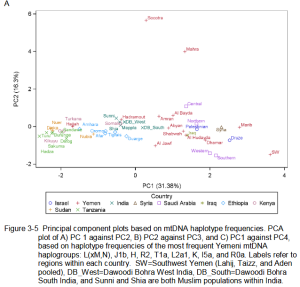

So as to ensure the accuracy and replicability of our admixture analysis, we will broadly repeat the steps above with a control population. For this purpose, we will utilize peninsular Arab samples from the Global25_PCA_modern datasheet as our Target group, including Yemeni Jews and Mahra individuals.

To start, we shall aim to identify the “purest” Sub-Saharan African reference population available for our Arabian Target population. We will achieve this by first conducting a Distance analysis on the Vahaduo Admixture JS program, using as our Source populations the ancient African samples listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet (again excluding the aforementioned ancient African samples with substantial Eurasian ancestry). We then take note of the top eight African samples with whom our Target population shares the closest genetic ties. We are only interested in the top eight results because these are the groups that are most likely to have contributed genes to our Target population.

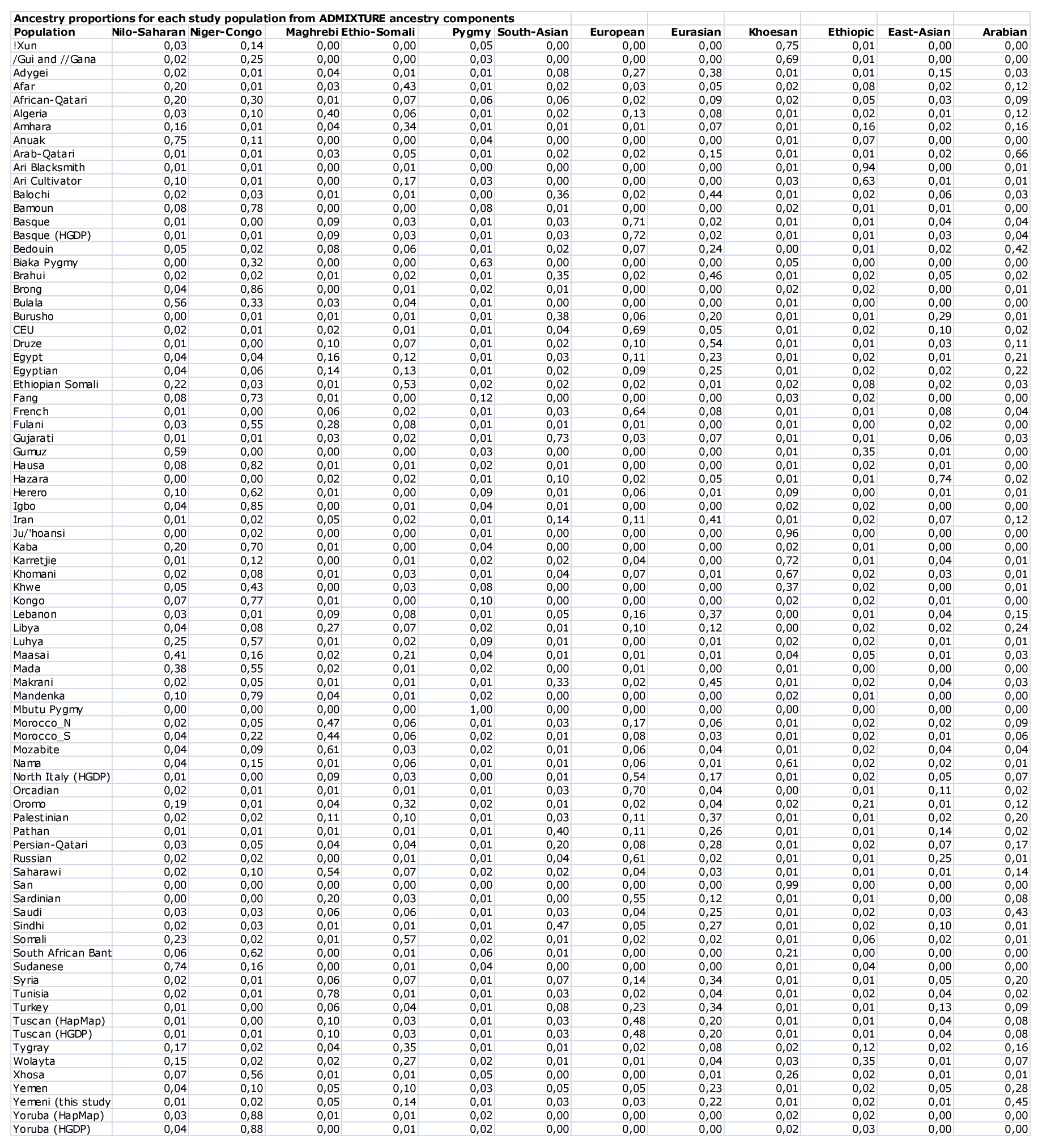

Next, we scour the existing genetic literature to find out which of these eight African proxy groups has the least documented non-African admixture. This necessary step will help us avoid depressing Eurasian ancestry/inflating Sub-Saharan African admixture in our Arabian cohort. According to Wang et al. (2020)’s admixture analysis, the COG_Kindoki_230BP:KIN002 sample from the Democratic Republic of the Congo has the least Eurasian admixture (red component):

We have thus found our “pure” Sub-Saharan African proxy sample for our examined Arabian individuals. This discovery informs us that the ancient contact population which contributed most of the Sub-Saharan African admixture in the Arabian peninsula (as represented by Congo Kindoki 230BP) was different from that which did the same in the Horn of Africa and Nile Valley (as represented by Kakapel 300BP) — a fact which is especially clear when we perform a two-way Vahaduo Multi analysis with peninsular Arab individuals, Afro-Asiatic speakers from the Horn, and Maghrebis, using the COG_Kindoki_230BP sample as our Sub-Saharan African Source population and the ancient Egyptian EGY_Late_Period sample as our ancient Eurasian Source population. The peninsular Arab samples wind up showing the highest average Niger-Congo ancestry in comparison to the other examined Afro-Asiatic-speaking groups, confirming their preference for this component as their main source of ancient Sub-Saharan African admixture:

Now, we will carry out a Vahaduo Single analysis, using as our Source populations all of the ancient non-African samples listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet, except those with non-trivial Sub-Saharan African admixture. This step identifies the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity sample as the predominant Eurasian ancestry borne by virtually all of the examined Arabian individuals (see here).

We will end by running a Vahaduo Multi analysis, using Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity as our “pure” ancient non-African reference sample and Congo Kindoki 230BP as our “pure” ancient African reference sample. The analysis produces acceptable Distance fits of <9%, with a sensible estimated average African admixture of ~17%. We may also note that the Mahra samples from Yemen have the least Sub-Saharan African admixture. This is consistent with previous research, which has established that Mahra individuals are on average the “purest” living Semites, having retained the most ancient Natufian ancestry and the lowest extraneous genetic influences (cf. Vyas (2017)).

Conversely, when a Vahaduo Multi analysis is conducted using KEN_IA_Deloraine — the ancient African sample with whom our Arabian individuals showed the greatest genetic affinity in the Vahaduo Distance analysis above (except Emiratis, most of whom preferred instead the COG_NgongoMbata_220BP ancient African sample) — the Arabian individuals appear to have a more elevated Sub-Saharan African admixture of ~19% on average (see here). If we consult again Wang et al.’s genome analysis, it is clear why that is: the early Bantu sample from the Deloraine farm in Kenya harbors substantial Eurasian admixture (red component) specifically related to Arabians, which, compared to other ancient African samples, is bringing it genetically closer to the modern Arabian individuals. This again highlights the importance of using ancient African proxy groups that have as little Eurasian admixture as possible.

Step 10: Re-confirm our findings using other ancient Egyptian samples

As a penultimate step, we will repeat our Vahaduo Admixture JS analysis using other ancient Egyptian samples in lieu of the EGY_1879BCE cohort. Although all of our modern Afro-Asiatic-speaking samples from the Horn demonstrated a clear preference for EGY_1879BCE in the Vahaduo Single analysis in Step #3 above, EGY_1879BCE is not listed on Eurogenes’ official Global25_PCA datasheet. We must therefore re-confirm our findings, this time using Global25’s official ancient Egyptian samples.

To start, we shall carry out a Vahaduo Distance analysis on all of the Eurasian samples listed on the Global25_PCA datasheet. Doing so will help us identify which of these ancient specimens our modern Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking individuals share the nearest affinity with. The Distance analysis indicates that our Afro-Asiatic speakers show a preference for the Levant_Beirut_IAIII_Egyptian:SFI-44 cohort followed by EGY_Late_Period:JK2134, which are ancient Egyptian samples dating from the Iron Age and later Dynastic epoch, respectively (see here).

We will now perform a Vahaduo Multi analysis, utilizing the Iron Age Levant_Beirut_IAIII_Egyptian:SFI-44 sample in place of the earlier Dynastic period EGY_1879BCE sample:

As can be seen in the table above, our Afro-Asiatic-speaking samples again wind up with almost the same average non-African ancestry (just over 70%), with approximately 27% Sub-Saharan African admixture and around 3% North African Iberomaurusian/Taforalt admixture. The average Distance fit is also similar. However, the apportionment of the Eurasian ancestries differs appreciably from before. The frequency of the ancient Egyptian component increases about 10 percentage points, going from an average of 18% to 28.1%. Additionally, the average frequency of the Levantine Natufian component rises over 10 percentage points, spiking from 20.9% to 31.3%. These boosts ultimately come at the expense of the European-related Steppe component and the East Asian component, which, respectively, drop from an average of 11.3% to 0% (~11 percentage points) and 22.6% to 12.6% (10 percentage points). Hence, the Steppe and East Asian components appear to be embedded within the Iron Age Levant_Beirut_IAIII_Egyptian cohort, representing constituent elements of that sample.

These changes inform us that:

1. The northern Egyptian population to which the earlier Dynastic period specimen EGY_1879BCE (i.e., the Middle Kingdom nobleman Nakht-Ankh) belonged had not yet interbred with the peoples who brought the European Steppe and East Asian-related ancestries to the Nile Valley, nor with the folks responsible for the Sub-Saharan African admixture element. This is also suggested by Vahaduo Multi analysis of ancient Egyptian individuals, which reveals that EGY_1879BCE only bore embedded Natufian (~81%) and Anatolian Neolithic ancestry (~19%):

2. By the time of the Iron Age Egyptian specimen Levant_Beirut_IAIII_Egyptian:SFI-44, these newcomers had largely been absorbed. From the cumulative data available, we may presume that this assimilation process was concentrated in northern Sudan and southern Egypt since the older Cushites of the Pastoral Neolithic — who seem to have originated from northern Sudan; see Wang et al. (2022) — already bore Steppe and East Asian components, as well as a minor Sub-Saharan African admixture element and a tiny Iberomaurusian admixture.

We will finish by conducting the same Vahaduo Multi analysis on the later Dynastic-era EGY_Late_Period:JK2134 sample, which the Afro-Asiatic speakers of the Horn also appear to favor. Predictably, the end result is virtually identical to the Levant_Beirut_IAIII_Egyptian:SFI-44 Multi analysis, with only incremental differences in Distance fit and ancestral component frequencies (see here). This apprises us that the Iron Age Egyptian profile actually dates earlier, to at least the later Dynastic period. It also lets us know that our interpretations vis-a-vis the EGY_1879BCE sample are correct.

When we perform the same confirmatory Vahaduo Multi tests on the Coptic Egyptian samples and northern Egyptian (Cairo and Mansoura) samples from IllustrativeDNA and the Muslim Egyptian samples from Eurogenes, alternately using the later Dynastic period EGY_Late_Period:JK2134 sample and Iron Age Levant_Beirut_IAIII_Egyptian:SFI-44 sample as our ancient Egyptian Source population in place of the earlier Dynastic period EGY_1879BCE cohort, the Coptic and northern Egyptian samples have ballooned Distance fits approaching 15%. By contrast, the general Muslim Egyptian samples maintain acceptable Distance fits of <9%. Hence, Coptic Egyptians and northern Egyptians indeed appear to derive most of their ancestry specifically from the earlier Dynastic period Egyptians, as represented by the EGY_1879BCE sample:

Step 11: Consolidate our findings for all local Afro-Asiatic speakers

Finally, to conclude our admixture study, we shall distil our findings by grouping all local Afro-Asiatic speakers (Horn African and North African alike) into one Vahaduo Multi table. This will allow us to more easily observe and describe broad trends in the data, and to spot any patterns or relationships that we may have overlooked.

From the data table above, we can discern three general ancestry patterns:

Besides the foregoing, we may also note that the Elmolo, a vestigial Cushitic-speaking group inhabiting Kenya, carry similar ancestral elements as the Horn’s Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations. They are distinguished by a substantially higher Sub-Saharan African admixture (~52% on average), which primarily consists of the “pure” ancient Nilo-Saharan element (Kakapel 300BP) followed by the “pure” ancient East African Hunter-Gatherer element (MWI_Chencherere). This is consistent with a heavy absorption of local Nilotic and forager individuals. Furthermore, the South Omotic-speaking Ari seem to derive the bulk of their ancestry from the Sub-Saharan African components (98%). This proportion is probably an overestimation since the Ari sample (taken from IllustrativeDNA) has a grossly unrealistic Distance fit of ~40%.

We will end by performing another Vahaduo Multi analysis on our Afro-Asiatic-speaking samples. This time, we shall employ the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity cohort as a Source population so as to quantify the amount of modern Arabian admixture present in our Target populations:

The data table above affirms that the Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations of the Horn, as well as Coptic Egyptians and northern Egyptians, do not bear any recent admixture from the Arabian peninsula. All of the examined Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking individuals and Coptic and northern Egyptian individuals have a 0% frequency of the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity component, an ancestral element typical of contemporary peninsular Arabs. This suggests that most of the gene flow from Arabia into Northeast Africa predates the Islamic era. On the other hand, Muslim Egyptians and Libyans do harbor this Arabian component at low frequencies of around 17% and 19%, respectively. In the Maghreb, average frequencies of this Arabian element are a bit lower, except among the Arabic-speaking Rbaya of Tunisia. Rbaya individuals on average carry the Levant_Tell_Qarassa_Early_Antiquity component at an elevated percentage of 44%. This strongly supports their traditions of descent from Arab forefathers. Intriguingly, most persons from the Arabic-speaking Douz community in Tunisia also have high frequencies of this Arabian ancestral component, in keeping with their own traditions of descent from Arab settlers.

Conclusion

The admixture analysis above tells us a number of things about the biogenesis of the modern Cushitic, Ethiosemitic and North Omotic-speaking populations of the Horn of Africa. We may summarize these key findings as follows:

11 Saturday Mar 2023

Tags

Abdel Monem A. H. Sayed, Adulis, AECR, Afro-Asiatic, Ahmed El-Batrawi, Ahmed Ibrahim Awale, Alula, Amelia Edwards, ancient DNA, Ancient Egypt, ancient inscriptions, Antiquities Service of Egypt, Arrian of Nicomedia, Ati, Auguste Mariette, Axumite Kingdom, Édouard Naville, Barbaria, Bia-Punt, Book of Gates, Boswellia frereana, Carleton Coon, Caterina Cozzolino, Caucasoid, Cushitic, D'mt, Dalbergia melanoxylon, David O’Connor, Deir el-Bahri, Dimitri Meeks, Diodorus Siculus, Egyptian pantheon, El-Osbolé, Emmett Sweeney, Epiphanius of Constantia, Eric Robson, Ernest-Théodore Hamy, Ernesto Schiaparelli, F. Nigel Hepper, Flinders Petrie, frankincense, G. Billy, G. W. B. Huntingford, Gaston Maspero, George A. Hoskins, George Andrew Reisner, Georges Révoil, Giuseppe Sergi, Grafton Elliot Smith, Grand Procession, Hamitic, Hathor, Hatshepsut, Heinrich Karl Brugsch, Horus, Hyphaene thebaica, James Bruce, Johannes Maria Hildebrandt, John Desmond Clark, Kathryn Bard, Kenneth Kitchen, Laas Geel, Lady of Punt, Land of Punt, Lionel Casson, Medri Bahri, Meroitic culture, Mersa Gawasis, myrrh, Nathaniel Dominy, Neville Chittick, Northeast Africa, Palermo Stone, Papio hamadryas, Perahu, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Precambrian, PROTA, Red Sea, Richard Pankhurst, Robert Bennett Bean, Robert Hoyland, Rodolfo Fattovich, Saww, Solomonid Dynasty, Stanley Balanda, stela, Ta netjer, Theodor von Heuglin, Toby Wilkinson, Wadi Gawasis, Zoscales

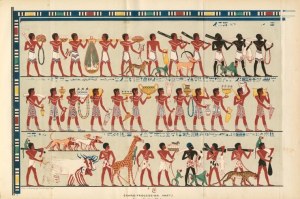

The Land of Punt was a major civilization in the ancient world. Located to the south and east of the Nile Valley, it was Dynastic Egypt’s main trading partner and the source of much of the frankincense, myrrh and other coveted products that were used by the Pharaohs in their traditional rituals and ceremonies. According to the Egyptian First Dynasty rulers or Horus-Kings, Punt (Ta netjer or “God’s Land”) was also their ancestral homeland.

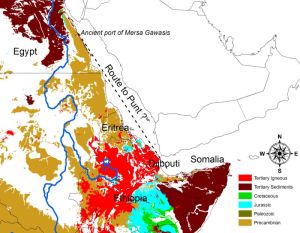

Given its historical importance, Egyptologists have long debated just where exactly this mysterious territory was situated. The riddle appeared to have been finally solved in 2010, when preliminary isotopic analysis narrowed down the prospective locations to present-day Eritrea. However, follow-up isotopic work as well as DNA studies conducted since then, analysis of clay from pots that were brought to Egypt from Punt, and little-known botanical evidence and epigraphs firmly locate the ancient land in a broader region stretching from northern Somalia, Djibouti and the Eritrea/Ethiopia corridor to northeastern Sudan. The recent discovery of the first actual Puntite artifacts and their similarity to those of ancient Egypt has, in particular, confirmed the close ties between both areas.

Route to Punt

One of the key factors in pinpointing the location of the Land of Punt is its geographical proximity to ancient Egypt. In this regard, scholars have often indicated that the territory was situated to the south and east. But what exactly do they base this on?

In the 1850s, the Antiquities Service of Egypt discovered hieroglyphic texts in the vicinity of Thebes (Luxor) in Upper Egypt. These inscriptions identify Punt as a source of aromatics found to the east of Egypt. This, in turn, would prompt the Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch to postulate that the ancient land was located in the Arabian peninsula. A few years later, his colleague the archaeologist Auguste Mariette came upon geographical lists at the Karnak Temple, which had been left by the Pharaoh Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty (r. 1458–1425 BCE). These hieroglyphics include Punt among the territories that lay to the south of Egypt. The Egyptologist Abdel Monem A. H. Sayed explains:

The first lists of this kind, and the most comprehensive, are those of Thutmoses III, where the regional and site names are arranged in a manner coinciding with their geographical locations.

The list of toponyms of the African side of the Red Sea begins with the heading Kush, the Egyptian name for Upper Nubia. Under this heading are recorded 22 toponyms. Then comes the regional name Wawat or Lower Nubia, with 24 toponyms listed under it. After that, the list begins again from the south, recording regional and site names closer to the Red Sea shore. The regional name Punt is mentioned as a heading for 30 toponyms. After Punt comes Mejay as a heading of 17 toponyms. Lastly comes the regional name Khaskhet extending along the Red Sea shore of Egypt, with 22 toponyms listed (Schiaparelli 1916, 115-9).

This clear hieroglyphic account allows the following important deductions[…] The relation between Punt and the other regional names in the list (Kush, Wawat, Mejay and some of the toponyms under the heading Khaskhet), of which the African locations are agreed among Egyptologists, shows clearly that in the time of Thutmoses III Punt was the most southerly region and adjacent to the Red Sea coast. This is of great value for locating Punt during the New Kingdom in general, and the time of Queen Hatshepsut in particular, with which I deal later.

A 26th Dynasty stela was also recovered from the ancient site of Dafnah (Daphnae) near the Egyptian Delta, which contains an inscription stating that “when rain falls on the mountain of Punt, the Nile floods.” This is a clear allusion to the northern Ethiopian highlands, around Lake Tana where the Blue Nile rises (cf. Sayed (1989)). The Papyrus of Hunefer, a 19th Dynasty document by an Egyptian royal scribe, strengthens this association, for it too includes the Blue Nile within the confines of Punt. Van Auken (2011) notes:

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote, “Egypt was the gift of the Nile.” Three tributaries created this amazing river. The first is the White Nile, a long gentle river flowing from Lake Victoria — a high mountain lake bordered by Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. This tributary joins with the shorter but more voluminous and nutrient-richer Blue Nile, springing from Lake Tana in Ethiopia. And in ancient times, a third tributary joined these two, the Yellow Nile flowing from the eastern highlands of Chad. The Yellow Nile is now dry but was once a part of this trinity of rivers creating the ancient Nile.

Each year during the rainy season, the ancient Nile River would overflow its banks and inundate Egypt; as it retreated, it left behind nutrient-rich black silt that made Egypt one of the most fertile lands in recorded history. Today, two dams now control the Nile — there is no flooding and no rich silt fertilizer.

Around this river of life-giving water grew one of the greatest cultures on the planet. The ancient Egyptians called the river Iteru, meaning “Great River”; the modern name comes from the Greek Neilos (Nilus in Latin), transliterated to Nile.

The Edfu Text, found in the Horus Temple in Edfu, and the Papyrus of Hunefer tell the story of a “hill people” who became the first settlers of this region. “We came from the beginning of the Nile where god Hapi dwells at the foothills of the Mountains of the Moon.” The Mountains of the Moon are likely those that contain Lake Tana in ancient Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia), the origin of the Blue Nile. This name may be traced back to a Greek ruler of late Egypt, Ptolemy, and the use of the name “Mountains of Selene,” the moon goddess of the Greeks.

Coupled with some of the floral and faunal evidence discussed below, Mariette’s discovery and the Dafnah tablet helped shift scholarly opinion as to where Punt was situated (including eventually that of Brugsch himself) away from a hypothesized Arabian location to the adjacent Horn of Africa.

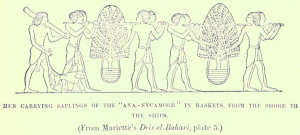

The Palermo Stone contains the earliest hieroglyphic description of an ancient Egyptian expedition to the Land of Punt, during the Fifth Dynasty (Sci-News).

Cozzolino (1993) enumerates over 50 other hieroglyphic inscriptions relating to the Land of Punt, and a few additional engravings have subsequently been discovered. The earliest of these writings is the Palermo Stone. It informs us that an ancient Egyptian expedition to Punt brought back 80,000 measures of ‘ntiyw (a particular type of incense), among other items, during the thirteenth regnal year of Sahure (ca. 2445 BCE), the second Pharaoh of the Old Kingdom’s Fifth Dynasty. Unfortunately, the Palermo Stone does not specify where Punt itself was located. We do, however, have an idea of how Sahure’s men got there. In 2002, an inscribed block was found at the pyramid of Sahure in the Abusir necropolis, with two of its registers depicting the arrival of ancient Egyptian cargo vessels transporting goods from Punt. From this, we know that the Sahure expedition was carried out by sea rather than overland. Punt was therefore not a landlocked territory.

A Sixth Dynasty inscription provides an even clearer indication of the route that the ancient Egyptians took to get to Punt during the Old Kingdom. Phillips (1997) notes that Pharaoh Pepi II or Neferkare (2278/2269–2184/2175 BCE) dispatched one of his expedition leaders, Pepinakht, to retrieve the body of the official Anankhti, who had been killed by bedouins in the Eastern Desert (the “desert of the Asiatics”) while overseeing the construction of a ship intended for another commercial expedition to Punt. Thus, the particular water route that was favored by the ancient Egyptian rulers appears to have been via the Red Sea. This is confirmed by a later, Middle Kingdom rock inscription at Wadi Hammamat from the reign of Pharaoh Mentuhotep III or Senekhkere (r. 2004–1992 BCE) of the Eleventh Dynasty. According to the chief treasurer Henu, he was ordered by the king to build a vessel destined for Punt along the Red Sea littoral:

[My lord, life, prosperity] health[…] sent me to dispatch a ship to Punt to bring for him fresh myrrh from the sheiks over the Red Land, by reason of the fear of him in the highlands. Then I went forth from Koptos upon the road, which his majesty commanded me…

I went forth with an army of 3,000 men. I made the road a river, and the Red Land (desert) a stretch of field, for I gave a stretch of field, for I gave a leathern bottle, a carrying pole[…], 2 jars of water and 20 loaves to each one among them every day. The asses were laden with sandals[…]

Then I reached the (Red) Sea; then I made this ship, and I dispatched it with everything, when I had made for it a great oblation of cattle, bulls and ibexes.

Now, after my return from the (Red) Sea, I executed the command of his majesty, and I brought for him all the gifts, which I had found in the regions of God’s-Land. I returned through the ‘valley’ of Hammamat, I brought for him august blocks for statues belonging to the temple. Never was brought down the like thereof for the king’s court; never was done the like of this by any king’s-confidant sent out since the time of the god.

In 1971, the Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen demonstrated the feasibility of such ancient travel down the Red Sea coast by charting an actual itinerary to get to Punt. This maritime gazetteer includes 80 possible anchorage points, as well as the intervening distances between them. It stretches from the Port of Sudan to northern Eritrea, a broad region that Kitchen suggests was coextensive with the Land of Punt.

So we know from the existing hieroglyphic texts that the ancient Egyptians preferred to reach Punt by water, and through the Red Sea specifically. We also know that this navigation was doable. The question is, what actual port did the ancient Egyptians use for these trading expeditions once they had finished constructing their vessels? A stela that was discovered at Wadi Gawasis (Wadi Gasus) provides an answer. Erected by Khentkhetwer, an official under the Twelfth Dynasty Pharaoh Amenemhet II or Nubkaure (r. 1922–1878 BCE), it contains an engraving that explicitly identifies Saww as the port where Khentkhetwer and his men arrived after their voyage to Punt. The Khentkhetwer stela inscription reads:

Giving divine praise and laudation to Horus[…], to Min of Coptos, by the hereditary prince, count, wearer of the royal seal, the master of the judgement-hall Khentkhetwer[…] after his arrival in safety from Punt; his army being with him, prosperous and healthy and his ships having landed at Sewew (Saww). Year 28.

Wooden cargo boxes labeled “wonderful things of Punt”, which were discovered at Mersa Gawasis, the ancient Egyptian port of Saww (Traveltoeat).